constructionism, textualism, and originalism

|

Jack (I think) suggested recently that there's a problem with "originalism". I can't remember whether his complaint was that it's a flawed concept, in itself, or that it's simply a pretense by which a justice justifies their own meaning for a given law by yapping about the "intentions" of the authors/adherents/enacters [⛧]. Correct me if I've screwed it up, Jack. It seems completely reasonable to me that a judge (or justice) would start out with and evolve a typical "method" by which they do their job. So, it's unclear to me what's wrong with originalism or textualism. (My brief googly suggested there are flaws with "strict construction". So, maybe we can ignore that one.) This article <https://www.salon.com/2020/09/22/trump-supreme-court-front-runner-amy-coney-barrett-belongs-to-group-that-inspired-handmaids-tale/> claims Judge Barrett is a "strict constructionist", by which I'm guessing he means she's really either originalist or textualist. But what I'm missing are the *other* "methods". What contrasts with originalist and textualist? Any clues for the clueless would be very welcome. [⛧] There's a word out there that I'm spacing. What's a synonym to "swear by", like when you say you "follow a creed" or whatever? -- ↙↙↙ uǝlƃ - .... . -..-. . -. -.. -..-. .. ... -..-. .... . .-. . FRIAM Applied Complexity Group listserv Zoom Fridays 9:30a-12p Mtn GMT-6 bit.ly/virtualfriam un/subscribe http://redfish.com/mailman/listinfo/friam_redfish.com archives: http://friam.471366.n2.nabble.com/ FRIAM-COMIC http://friam-comic.blogspot.com/

uǝʃƃ ⊥ glen

|

Re: constructionism, textualism, and originalism

|

Hi Glen,

I don’t know how one defines it as a method, but the approach I usually hear contrasted with Originalism comes associated with “living document” language. The idea being that any legal statement cannot take any meaning but in the context of its time (socially accepted norms, available knowledge of facts, social and material technologies and institutions, demographics and conditions of living, etc.), and that if those conditions have changed, there is no sensible way in which an appropriate meaning of a text can be derived without reference to the current context. This seems to me sort of obvious and inescapable, in the sense that pre-Shakespeare, one would have used “nice” to mean a sharp, burning or cutting pain, but to expect or demand that everyone who heard the word today know that that was its intended meaning would be absurd. Likewise that “people” in “we the people” meant the anglo male landed gentry of the time, as opposed to “people” as the term would be used in non-Republican society today. An interesting problem this poses for me is how correctly to make the argument that a constitution should be a reasonably-stable, but reasonably-adaptable, document to reflect the sense of right in the society of its time, but not be tossed around by the winds of populism or fads or momentary cultural battles like identity contests or post-modern depredations of everything. To assert that the court should be responsive to the norms of the day, but that it should not be politicized (in the sense of, just an effector arm of political parties), when parties are the overwhelmingly dominant organizational structure throughout the modern era in the US, seems to be saying that the SCOTUS should have an independent, parallel, distributed sensor network to the state of the society, somehow protected from this massive gorilla of a power structure that has come to subsume every other institution. I like the idea of autonomous, parallel, distributed channels, but how to design one is not a question on which I think I have insight. Eric > On Sep 22, 2020, at 3:02 PM, uǝlƃ ↙↙↙ <[hidden email]> wrote: > > > Jack (I think) suggested recently that there's a problem with "originalism". I can't remember whether his complaint was that it's a flawed concept, in itself, or that it's simply a pretense by which a justice justifies their own meaning for a given law by yapping about the "intentions" of the authors/adherents/enacters [⛧]. Correct me if I've screwed it up, Jack. It seems completely reasonable to me that a judge (or justice) would start out with and evolve a typical "method" by which they do their job. So, it's unclear to me what's wrong with originalism or textualism. (My brief googly suggested there are flaws with "strict construction". So, maybe we can ignore that one.) > > This article <https://www.salon.com/2020/09/22/trump-supreme-court-front-runner-amy-coney-barrett-belongs-to-group-that-inspired-handmaids-tale/> claims Judge Barrett is a "strict constructionist", by which I'm guessing he means she's really either originalist or textualist. > > But what I'm missing are the *other* "methods". What contrasts with originalist and textualist? Any clues for the clueless would be very welcome. > > > [⛧] There's a word out there that I'm spacing. What's a synonym to "swear by", like when you say you "follow a creed" or whatever? > > -- > ↙↙↙ uǝlƃ > > - .... . -..-. . -. -.. -..-. .. ... -..-. .... . .-. . > FRIAM Applied Complexity Group listserv > Zoom Fridays 9:30a-12p Mtn GMT-6 bit.ly/virtualfriam > un/subscribe https://linkprotect.cudasvc.com/url?a=http%3a%2f%2fredfish.com%2fmailman%2flistinfo%2ffriam_redfish.com&c=E,1,cs6joSIjNZCXbbMLdI6hNTgcKoCSDqkn6yddMm5-bfLgCp8dtD-adEN9LefTFAdy240dbll5QrxirafeRMZp2dN2CcSo5YLYGVcmVU7kR1v6&typo=1 > archives: http://friam.471366.n2.nabble.com/ > FRIAM-COMIC https://linkprotect.cudasvc.com/url?a=http%3a%2f%2ffriam-comic.blogspot.com%2f&c=E,1,jXqRAh65ncY27fyjjuhG78PwvaNvUpAFrGyAkY2sOpp4KM-UkfdFZjiETwykzhIN44BJnOFV7k9dBQNeee8YFeZTPjWbJpp0JmKUiB-Q&typo=1 - .... . -..-. . -. -.. -..-. .. ... -..-. .... . .-. . FRIAM Applied Complexity Group listserv Zoom Fridays 9:30a-12p Mtn GMT-6 bit.ly/virtualfriam un/subscribe http://redfish.com/mailman/listinfo/friam_redfish.com archives: http://friam.471366.n2.nabble.com/ FRIAM-COMIC http://friam-comic.blogspot.com/ |

|

Excellent! That helps. It seems reasonable to think one can be a "living document textualist". I.e. you first identify the (perhaps wide-ranging) set of relevant *enacted text*. Then you have some rules by which you apply/infer meaning and implications of that text. An originalist would differ from a livingist by grounding the text to the historical context in which it was enacted versus the current context, respectively. I think the categories aren't disjoint, though. My guess is both types would *have* to do some translations like your example of "nice". You can't do either context-grounding without some translation. So, it's more like a bias than a category.

Re: "the law" -- The entry on constitutionalism in my "American Conservatism" encyclopedia claims that the modern conception of a constitutional government is to *limit* the power of the government w.r.t. the governed individuals, most obviously in the separation of powers. And the author of the entry (Whittington) goes on to assert that a US addition to the modern conception is "the notion of the constitution as a fundamental law." What this might mean for the above context grounding would be something like an "upper ontology" https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Upper_ontology. The core facility of ontologies is the ability to (semi-automatically) translate from one lexicon to another, identifying the same concepts in spite of variation in the words used. If constitutions *are* some type of mechanism for objectively distinguishing *scopes* (individual vs. government), then what we mean by "law" is only *indicated* by the text, not ensconced *inside* the text ... some kind of indirect, Platonic, non-naive realist structure we're approaching with our various text documents. Re-reading that entry resuscitated the question about what freedoms the Democrats are trying to take away. Do *laws*, by which I mean that objective referent of the texts, primarily expand or limit freedoms? Laws like Obamacare seem to expand positive freedom *via* the negative freedom from (e.g.) pre-existing conditions. But conservatives hate Obamacare for some bizarre reason. And this takes me back around to the irritating question about mathematics, is it invented by us? Or discovered by us? Are laws something fundamental to the composition of collectives from individuals that we're discovering? Or are they prescriptive, arrogant attempts to *engineer* the world, imputed by the charismatic/influential/facile among us? If we could answer that, we'd have some hints to your question about parties vs. orthogonal access to the state of society. p.s. I've long been confused by the uptake of Maturana and Varela's autopoiesis by legal scholars. Why would they be attracted to what seems like theoretical biology to me? But perhaps there's more to the relationship between science and law than I've ever thought to be the case? Is law a kind of sociology? If so, then "theoretical law" and theoretical biology might not be so different. On 9/23/20 3:39 AM, David Eric Smith wrote: > I don’t know how one defines it as a method, but the approach I usually hear contrasted with Originalism comes associated with “living document” language. The idea being that any legal statement cannot take any meaning but in the context of its time (socially accepted norms, available knowledge of facts, social and material technologies and institutions, demographics and conditions of living, etc.), and that if those conditions have changed, there is no sensible way in which an appropriate meaning of a text can be derived without reference to the current context. > > This seems to me sort of obvious and inescapable, in the sense that pre-Shakespeare, one would have used “nice” to mean a sharp, burning or cutting pain, but to expect or demand that everyone who heard the word today know that that was its intended meaning would be absurd. Likewise that “people” in “we the people” meant the anglo male landed gentry of the time, as opposed to “people” as the term would be used in non-Republican society today. > > An interesting problem this poses for me is how correctly to make the argument that a constitution should be a reasonably-stable, but reasonably-adaptable, document to reflect the sense of right in the society of its time, but not be tossed around by the winds of populism or fads or momentary cultural battles like identity contests or post-modern depredations of everything. To assert that the court should be responsive to the norms of the day, but that it should not be politicized (in the sense of, just an effector arm of political parties), when parties are the overwhelmingly dominant organizational structure throughout the modern era in the US, seems to be saying that the SCOTUS should have an independent, parallel, distributed sensor network to the state of the society, somehow protected from this massive gorilla of a power structure that has come to subsume every other institution. I like the idea of autonomous, parallel, distributed channels, but how to design one is not a question on which I think I have insight. -- ↙↙↙ uǝlƃ - .... . -..-. . -. -.. -..-. .. ... -..-. .... . .-. . FRIAM Applied Complexity Group listserv Zoom Fridays 9:30a-12p Mtn GMT-6 bit.ly/virtualfriam un/subscribe http://redfish.com/mailman/listinfo/friam_redfish.com archives: http://friam.471366.n2.nabble.com/ FRIAM-COMIC http://friam-comic.blogspot.com/

uǝʃƃ ⊥ glen

|

Re: constructionism, textualism, and originalism

|

I have not read a lot about constitutional and or legal interpretation, but what I have read seems to be a very shallow echo of hermeneutics and exegesis philosophies and methods developed for religions texts, especially the Koran, Torah, and Bible. Maybe a course or two in literary hermeneutics should be prerequisite for getting a law degree and or a judgeship? I was part of a conversation recently with an ultra-liberal and arch-conservative that focused on 2nd amendment. The Lib stated that the 2nd applied only to militias and the kind of rifles owned by militia members at that point in history. A pretty familiar argument. The Con said this was wrong - that the 2nd is really about the populace having the means to overthrow a government that has become tyrannical. When written this meant semi-governmental militias with state of the art weaponry. Translated to today, that would mean Sheriff sanctioned "posses" / "militias" with RPGs, Stingers, and suitcase nukes. The beer was cold, the Valley Tan was smooth and the argument was long and heated, but friendly. davew Valley Tan — whisky brewed by Mormon pioneers from wheat and oats. Brigham Young had an exclusive license to distill it. Mark Twain and Brigham share a bottle or two when Twain visited. Sir Richard Burton shared same with Porter Rockwell when Burton passed through SLC. davew On Wed, Sep 23, 2020, at 8:36 AM, uǝlƃ ↙↙↙ wrote: > Excellent! That helps. It seems reasonable to think one can be a > "living document textualist". I.e. you first identify the (perhaps > wide-ranging) set of relevant *enacted text*. Then you have some rules > by which you apply/infer meaning and implications of that text. An > originalist would differ from a livingist by grounding the text to the > historical context in which it was enacted versus the current context, > respectively. I think the categories aren't disjoint, though. My guess > is both types would *have* to do some translations like your example of > "nice". You can't do either context-grounding without some translation. > So, it's more like a bias than a category. > > Re: "the law" -- The entry on constitutionalism in my "American > Conservatism" encyclopedia claims that the modern conception of a > constitutional government is to *limit* the power of the government > w.r.t. the governed individuals, most obviously in the separation of > powers. And the author of the entry (Whittington) goes on to assert > that a US addition to the modern conception is "the notion of the > constitution as a fundamental law." What this might mean for the above > context grounding would be something like an "upper ontology" > https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Upper_ontology. The core facility of > ontologies is the ability to (semi-automatically) translate from one > lexicon to another, identifying the same concepts in spite of variation > in the words used. If constitutions *are* some type of mechanism for > objectively distinguishing *scopes* (individual vs. government), then > what we mean by "law" is only *indicated* by the text, not ensconced > *inside* the text ... some kind of indirect, Platonic, non-naive > realist structure we're approaching with our various text documents. > > Re-reading that entry resuscitated the question about what freedoms the > Democrats are trying to take away. Do *laws*, by which I mean that > objective referent of the texts, primarily expand or limit freedoms? > Laws like Obamacare seem to expand positive freedom *via* the negative > freedom from (e.g.) pre-existing conditions. But conservatives hate > Obamacare for some bizarre reason. And this takes me back around to the > irritating question about mathematics, is it invented by us? Or > discovered by us? Are laws something fundamental to the composition of > collectives from individuals that we're discovering? Or are they > prescriptive, arrogant attempts to *engineer* the world, imputed by the > charismatic/influential/facile among us? If we could answer that, we'd > have some hints to your question about parties vs. orthogonal access to > the state of society. > > > p.s. I've long been confused by the uptake of Maturana and Varela's > autopoiesis by legal scholars. Why would they be attracted to what > seems like theoretical biology to me? But perhaps there's more to the > relationship between science and law than I've ever thought to be the > case? Is law a kind of sociology? If so, then "theoretical law" and > theoretical biology might not be so different. > > > > On 9/23/20 3:39 AM, David Eric Smith wrote: > > I don’t know how one defines it as a method, but the approach I usually hear contrasted with Originalism comes associated with “living document” language. The idea being that any legal statement cannot take any meaning but in the context of its time (socially accepted norms, available knowledge of facts, social and material technologies and institutions, demographics and conditions of living, etc.), and that if those conditions have changed, there is no sensible way in which an appropriate meaning of a text can be derived without reference to the current context. > > > > This seems to me sort of obvious and inescapable, in the sense that pre-Shakespeare, one would have used “nice” to mean a sharp, burning or cutting pain, but to expect or demand that everyone who heard the word today know that that was its intended meaning would be absurd. Likewise that “people” in “we the people” meant the anglo male landed gentry of the time, as opposed to “people” as the term would be used in non-Republican society today. > > > > An interesting problem this poses for me is how correctly to make the argument that a constitution should be a reasonably-stable, but reasonably-adaptable, document to reflect the sense of right in the society of its time, but not be tossed around by the winds of populism or fads or momentary cultural battles like identity contests or post-modern depredations of everything. To assert that the court should be responsive to the norms of the day, but that it should not be politicized (in the sense of, just an effector arm of political parties), when parties are the overwhelmingly dominant organizational structure throughout the modern era in the US, seems to be saying that the SCOTUS should have an independent, parallel, distributed sensor network to the state of the society, somehow protected from this massive gorilla of a power structure that has come to subsume every other institution. I like the idea of autonomous, parallel, distributed channels, but how to design one is not a question on which I think I have insight. > > -- > ↙↙↙ uǝlƃ > - .... . -..-. . -. -.. -..-. .. ... -..-. .... . .-. . > FRIAM Applied Complexity Group listserv > Zoom Fridays 9:30a-12p Mtn GMT-6 bit.ly/virtualfriam > un/subscribe http://redfish.com/mailman/listinfo/friam_redfish.com > archives: http://friam.471366.n2.nabble.com/ > FRIAM-COMIC http://friam-comic.blogspot.com/ > - .... . -..-. . -. -.. -..-. .. ... -..-. .... . .-. . FRIAM Applied Complexity Group listserv Zoom Fridays 9:30a-12p Mtn GMT-6 bit.ly/virtualfriam un/subscribe http://redfish.com/mailman/listinfo/friam_redfish.com archives: http://friam.471366.n2.nabble.com/ FRIAM-COMIC http://friam-comic.blogspot.com/ |

|

In reply to this post by David Eric Smith

Amy Coney Barrett's "originalist" doctrine may sound good — but it's incoherent https://www.salon.com/2020/10/19/amy-coney-barretts-originalist-doctrine-may-sound-good--but-its-completely-incoherent/ Merely more fodder for "methods". On Wed, 23 Sep 2020 06:39:13 -0400 David Eric Smith <[hidden email]> wrote: > I don’t know how one defines it as a method, but the approach I > usually hear contrasted with Originalism comes associated with > “living document” language. - .... . -..-. . -. -.. -..-. .. ... -..-. .... . .-. . FRIAM Applied Complexity Group listserv Zoom Fridays 9:30a-12p Mtn GMT-6 bit.ly/virtualfriam un/subscribe http://redfish.com/mailman/listinfo/friam_redfish.com archives: http://friam.471366.n2.nabble.com/ FRIAM-COMIC http://friam-comic.blogspot.com/

uǝʃƃ ⊥ glen

|

Re: constructionism, textualism, and originalism

|

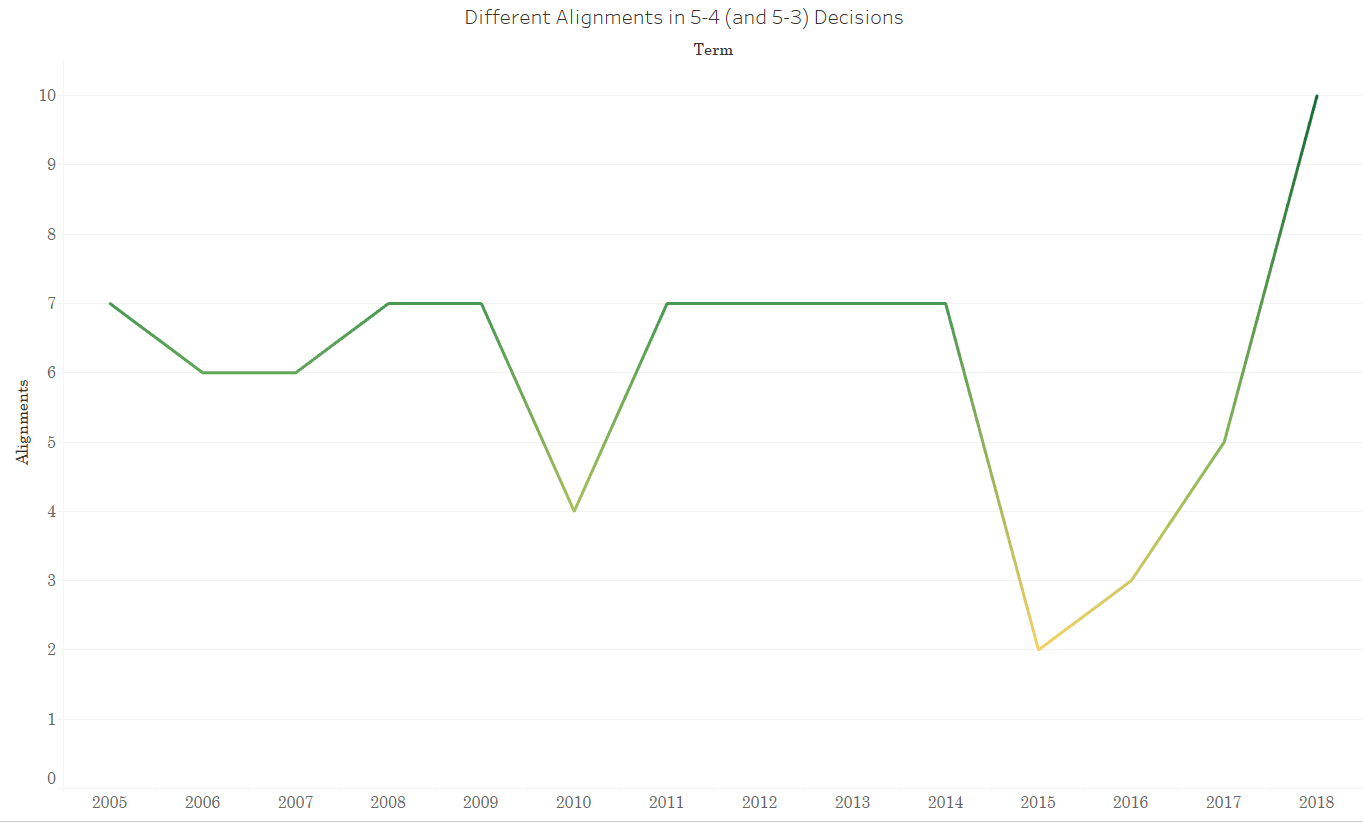

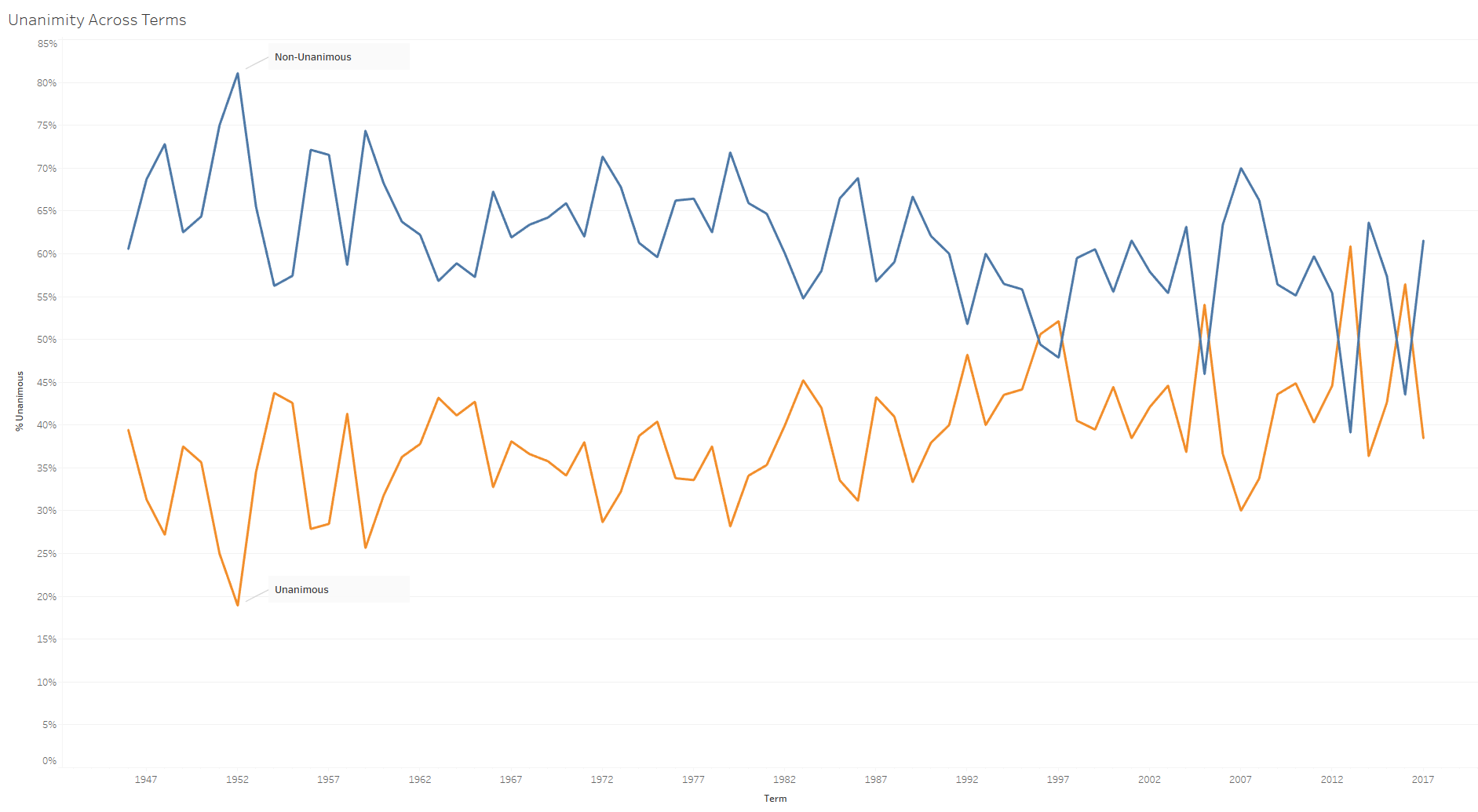

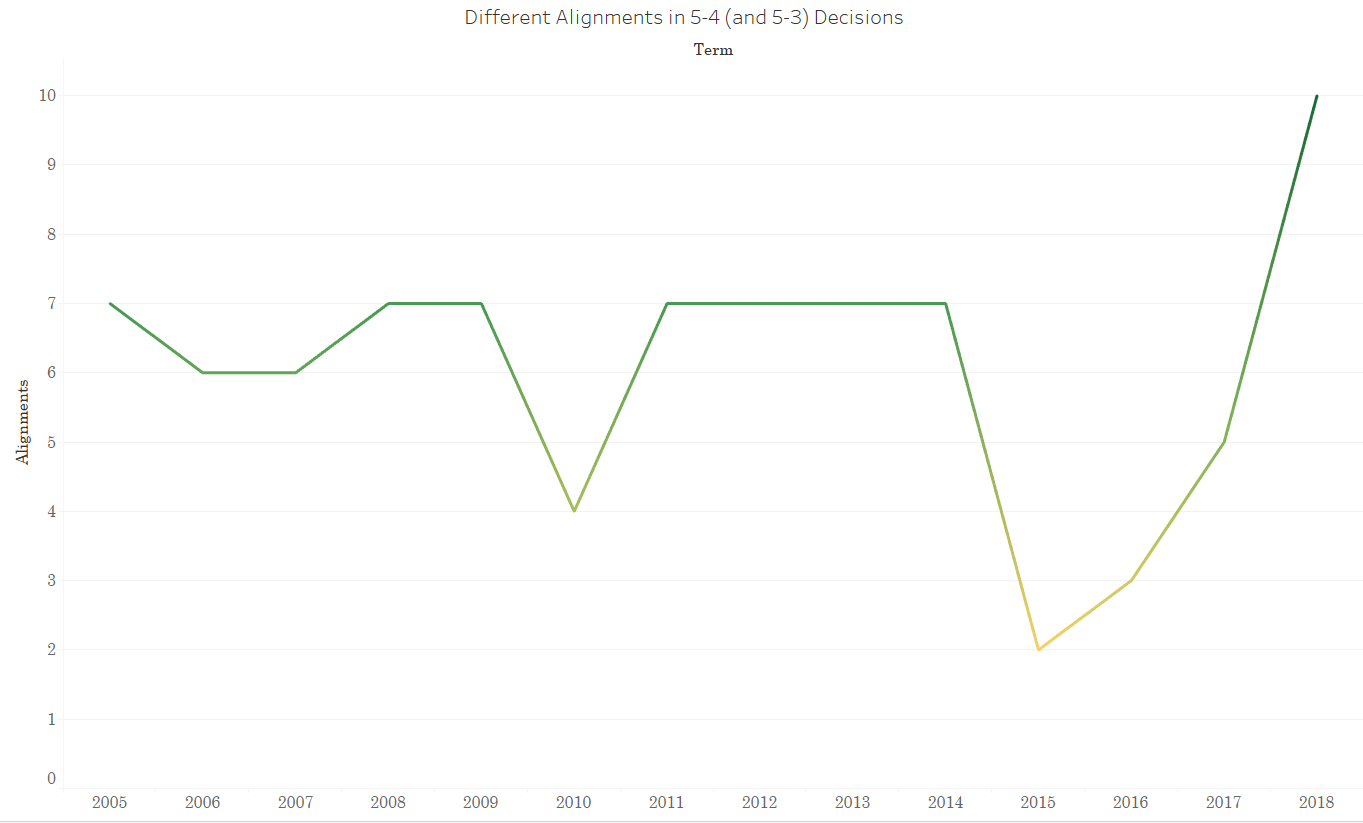

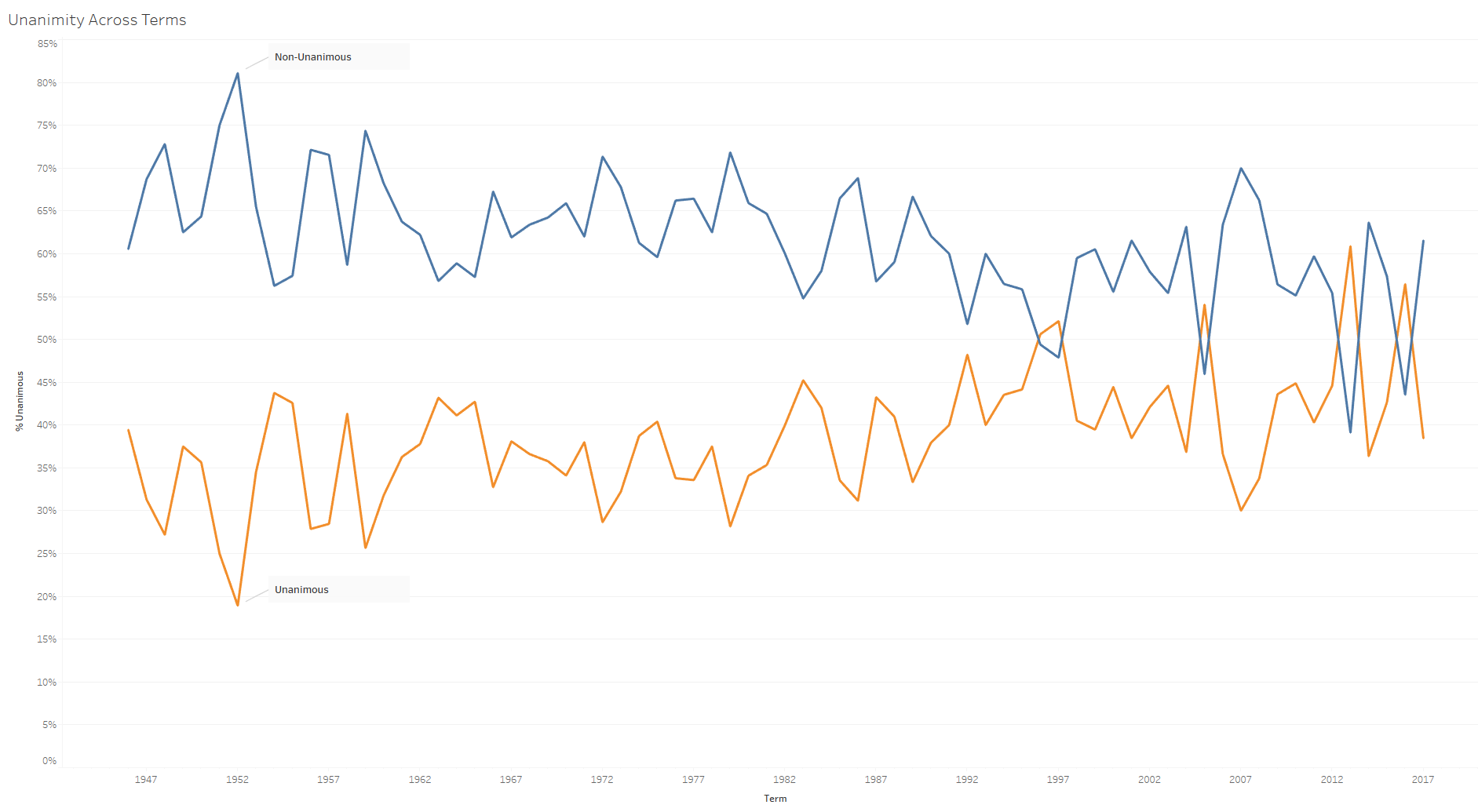

That article is baffling. Just because a method is hard doesn't mean it is an invalid method. Also, the focus on the particularly contentious issues masks the broad agreement about what most of the constitution meant at the time. We focus so much on the ideologically split decisions, but it is not unusual to have a year with 50% unanimous SCOTUS decisions (orange line below), and the number of decisions that split 5-4 between the "liberal" and "conservative' justices is small. In fact if you look at the graph with just one green line, it shows the number of configurations that made up 5-4 decisions during the term in question; in the final year shown (2018) every "conservative" justice served as a "swing vote" siding with the "liberal" justices for at least one decision, and vice versa. Also, beyond that, nothing in the article is about "Barrett's Originalism." It is broadsided attack about whether we can ever know what anyone meant by anything. I mean, if I go before a judge with a prenuptial agreement stating that all houses will be divided evenly in a divorce, and I argue that I'll take the main house and the vacation house, while my wife takes the doll house and the bird house.... odds are that the judge is going to make an originalist/textualist arugement towards the generally understood meaning of those words at the time the contract was signed, unless I can producing some extraordinary evidence that my wife understood those to be "houses" for the purposes of the contract at the time of the signing (such as explicit letters or voice recordings to that effect). Whether or not some randomly selected schmoes off the street would say that a "bird house" was a "house" on an academic questionairre would never enter into it. If I argued that while clearly those were not considered "houses" when the document was signed, but that last year Merriam Webster changed things to make it clear that a bird house was a house, the judge wouldn't care in the least about that. The judge would care about either a) the standard, understood legal meaning at the time of the signing, b) the meaning as understood by the particular signers of the document at the time, if evidence about that was availible, or c) the understood legal meaning today (following precedence of legal decisions that occured between then and now). Although, admittedly, the judge could also care what they thought the law should do, based on some other agenda. For example, which decision most empowered historically disadvantaged people (as some liberal judges are asserted to think today), or which decision most allowed for issues to be worked out by the people rather than the law (as Oliver Wendel Holmes supposedly prioritized). But those types of agendas don't generally impact mundane legal issues. I mean... people say things like "how do we really know how a word was pronounced in Shakespear's time?" as if it is a vacuous mystery... but, in fact, pronunciation was non-standard enough at the time that playrights routinely included notes explaining how to pronounce particular words in the play. Similary, much of our law is surrounded by explicit, well documented discussions among those who were writing and signing the legislation. There is wiggle room in some places, but in other places we have very clear records of what was intended, and why particular words were chosen. The problem with Barrett's Originalism is that we have no key examples of it to evaluate. She has a nice array of legal papers (I've read a few of them), but doesn't have an extensive record of actually deciding cases.  On Mon, Oct 19, 2020 at 9:55 AM glen <[hidden email]> wrote:

- .... . -..-. . -. -.. -..-. .. ... -..-. .... . .-. . FRIAM Applied Complexity Group listserv Zoom Fridays 9:30a-12p Mtn GMT-6 bit.ly/virtualfriam un/subscribe http://redfish.com/mailman/listinfo/friam_redfish.com archives: http://friam.471366.n2.nabble.com/ FRIAM-COMIC http://friam-comic.blogspot.com/ |

Re: constructionism, textualism, and originalism

|

A particular example:

EPIC SYSTEMS CORP. v. LEWIS (2017) That link will take you to the whole decision, my summary is below. Note that the dispute boils down to what the authors wanted the law to do vs how the law was written, in a situation where it is absolutely clear that the phrasing of the law was intended to restrict the power of the court. This summary is long, but hey, it's a 61 page decision, so this is still a lot shorter: Back in the late 1800's, arbitration was a tool used by labor to hold employers accountable. In the early 1900's, the courts were generally hostile to it. Congress acted to help the worker out by creating the Federal Arbitration Act (FAA) in 1925, which made clear that arbitration agreements were legal and required courts to enforce them. The courts complied, and there are lots of SCOTUS decisions declaring the FAA constitutional. Later on other labor laws were passed, including the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA) in 1935, which broadly protected workers rights to organize and engage in collective bargaining. Fast forward several decades, and now employers have figured out how to write arbitration agreements in their favor. In particular, they have started writing arbitration clauses that ban employees from turning complaints into class action suits. In the past, courts have generally declared such agreements legal, because the FAA was designed explicitly to make arbitration agreements strictly enforced, and the FAA is still law. The NLRA wasn't seen as conflicting with the FAA in such cases. Even 8 years ago, the National Labor Relations Board’s, which is charged with enforcing the FAA, was cool with that. Then 6 years ago, the Board's general council wrote up an argument that maybe the NLRA could conflict with the FAA, meaning that maybe class action lawsuits should be allowed, even if one-on-one arbitration agreements have been signed, because that would be better for workers, and the NLRA could be read that way sort of (even though it hadn't been read that way for the 77 years before). Many individual arbiters started to go with the Board's decision, class action suits started to appear. Some employers forced the suits to the appellate courts, arguing the whole thing was FUBAR. Later Board writings seemed to waffle on the issue, some court's thought they (the judge) had to defer to the board even if they (the judge) disagreed, other judges agreed with the board, others stuck with the 77 years of prior legal precedence. Eventually, this mess at the appellate court level led to contradictory decisions between various circuit courts, which is the type of thing that gets a dispute in front of SCOTUS. RBG and her 3 cosigners all say that the NLRA should be understood to have overridden the FAA in these types of situations, because there is an "and other stuff" clause in the NLRA. Plus, they note, the intent of Congress in writing the FAA was to help workers, and today's arbitration agreements sure don't help workers. [Note to Glen, this is a "living document" view for sure. Those legislators back in the '20s were trying to help particular people, and they wouldn't have wanted their law used to hurt those people in these changed times (this method states), and the court should take that into account, even if such a decision would upturn the law as written and as understood for the past 7 decades.] Gorsuch and his 4 cosigners disagree that the NLRA overrode the FAA in this case, and that's the only notable disagreement as to the facts. They agree the FAA's intent was to help workers, they agree this decision doesn't help workers. They agree that the FAA and NLRA protect union organizing, which would include union lawsuits, which are inherently collective lawsuits. But they don't think the Court is in a position to declare one-on-one arbitration agreements inherently illegal, which is what the employees are asking for, because the FAA exactly requires the court to not restrict the content of arbitration agreements and to enforce them as they are written. As there is a fairly reasonable way to read the NLRA as not conflicting with the FAA on that issue, and as SCOTUS precedence is to interpret laws as compatible whenever they can reasonably be read that way, these 5 justices are going to read the two laws as not conflicting in the way suggested (in line with the 77 years of prior legal precedence). Also, they think the Labor Relations Board's decision is pretty much bunk, because the Board doesn't exist to deal with the NLRA, it only exists to deal with the FAA, and so (the majority opinion asserts) the Board should have stuck as closely to the FAA's language and precedence as it could have. As Gorsuch puts it: "You might wonder if the balance Congress struck in 1925 between arbitration and litigation should be revisited in light of more contemporary developments. You might even ask if the Act was good policy when enacted. But all the same you might find it difficult to see how to avoid the statute’s application." [Note to Glen, this is a straightforward "originalist" view. We know - not just from the word used, but from extensive documentation of statements by the legislators at the time - that Congress exactly intended the law to require courts to enforce arbitration agreements as written. The law could be repealed or modified at any time by today's legislators, but in the meantime it is the job of the court (this method states) to stick to the law as written (unless there is a compelling argument that the law-as-written is unconstitutional, and no such argument was being made in this case).] On Wed, Oct 21, 2020 at 10:38 PM Eric Charles <[hidden email]> wrote:

- .... . -..-. . -. -.. -..-. .. ... -..-. .... . .-. . FRIAM Applied Complexity Group listserv Zoom Fridays 9:30a-12p Mtn GMT-6 bit.ly/virtualfriam un/subscribe http://redfish.com/mailman/listinfo/friam_redfish.com archives: http://friam.471366.n2.nabble.com/ FRIAM-COMIC http://friam-comic.blogspot.com/ |

«

Return to Friam

|

1 view|%1 views

| Free forum by Nabble | Edit this page |